How Opioid Pain Reliever Drugs Changed the Drug Addiction Scene

When we work to address the current drug addiction epidemic that has swept our country, we must accept a universal truth. The truth is that the mass introduction of opioid pharmaceuticals (and other addictive pharmaceuticals, for that matter) onto the drug scene has changed how drugs are accessed and misused. In fact, the heavy proliferation of addictive medicines which began in the late 1990s served to alter the face of the addiction scene forever.

For example, for decades the way that addicts obtained drugs was by going out on the streets and finding a dealer to buy drugs from. That is why such substances are called “street drugs.” But all of that has changed since pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors began to push addictive medications and since doctors started to prescribe them. Now we have an entire selection of legal drugs which are just as addictive, dangerous, and life-threatening as the illegal ones are. Our problem doubled almost overnight, splitting into areas of illegal and legal drug addiction crises which we must now address.

A New Problem to Tackle

The new problem to tackle is that drug users are finding more creative ways to get a hold of mind-altering drugs. Because tens of millions of Americans are taking potentially addictive prescription drugs every day, millions of addicts know that households everywhere likely have some mind-altering prescription drug tucked away in a medicine cabinet somewhere.

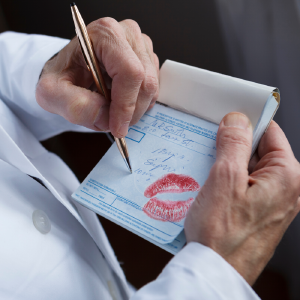

When the pharmaceutical opioid epidemic took off in the late-1990s and early-2000s, patient-addicts would “doctor shop,” meaning they would go to multiple doctors and pharmacies to fill several prescriptions, all under the guise of being a legitimate pain patient who needed the meds for pain.

But the implementation of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs cracked down on that problem. A PDMP is an advanced patient database that each state uses to track which patients receive what meds and at what locations.

In more recent years, as doctor shopping has become more difficult for addicts to get away with, pill addicts have turned to family members, loved ones, friends, co-workers, and neighbors—anyone who might have pills on hand. While this has been a trend for some time, a recent University of Michigan study published in the JAMA Network and discussed in U.S. News was the first research project that sought to uncover statistics and data on just how widespread this phenomenon is.

The Statistics

While it is impossible to determine how many people who have prescriptions for opioids are then robbed or manipulated out of those opioids by an addicted family member, we can get at this problem from another angle. We can use patient records from PDMP programs and insurance policies to determine how many individuals have legitimate prescriptions for painkillers who also have a family member who, at some point, attempted to doctor shop for opioids.

Do you see what this is getting at? With medical record keeping, PDMPs, and data assessment, we can determine if any patient has a family member who once doctor shopped. We can narrow this down further and examine accurately the current patients in the U.S. who have a legitimate prescription for opioid pain relievers, and we can determine how many of them have family members who engaged in unethical efforts to get hold of opioids at some point.

This information is incredibly valuable to us. If we know how many Americans are legitimately prescribed opioids and what percentage of those Americans are to some degree at risk (by having a family member who once doctor shopped and who now might try to go through their family member’s medicine cabinet), it follows logically that we can take steps to prevent the spread of opioid addiction.

According to the research, for every 176 patients who were prescribed an opioid in 2016, one of them had a family member who once showed up in either PDMP or insurance data for doctor shopping.

Let’s break those numbers down further.

The University of Michigan researchers analyzed no less than 1.5 million prescriptions for opioid pain relievers written in 2016 for 554,000 people who had family members covered under the same family insurance plan. Of those 1.5 million prescriptions, 8,485 were filled by a patient who also had a family member covered under the same insurance plan who at one point was caught doctor shopping.

Now let’s extrapolate those figures out to a national scale. There were 210 million opioid prescriptions written in 2016. Based off the above statistics, 1.2 million of those 210 million prescriptions went to households where one of the family members had once been caught doctor shopping. That’s a potential for 1.2 million different incidences where an opioid-addicted family member could have gotten into Mom’s or Dad’s or the spouse’s opioid pill bottle—possibly overdosing, possibly dying.

And what about all of the prescriptions that went to households where a family member had doctor shopped but wasn’t caught? We can only guess as to that figure.

Helping Family Members and Loved Ones Seek Treatment

What can we learn from this study? We can learn, first and foremost, that opioid prescribing is far too prolific in this country. Simply stated, we are sending out way too many opioids, and it is harming our family members and loved ones. One out of 176 opioid prescriptions going to a family with a potential opioid addict in the household is not a hefty sum, but extrapolate that over the hundreds of millions of opiate prescriptions doled out every year and the numbers do add up.

The first lesson here is to drastically reduce opioid prescribing—a task which has been slowly developing over the last few years. But perhaps even more important than that, we also have to improve our family unit in America. There is no reason why a family should be receiving a prescription for an opioid pain reliever if someone else within that family once needed opioids so badly that they went so far as to doctor shop to get them.

If you have a family member or loved one who is struggling with an opioid habit, the most important thing to do is to get them help and to do so as soon as possible. With residential treatment, even the direst of opioid addictions can be overcome. Don’t live with opioid addiction within your household. It will always get worse if nothing is done to address it. If your loved one has had to resort to doctor shopping, it’s time to talk to them about getting off of opioids. It’s time to speak with them about getting help.

Sources:

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2733179

- https://www.usnews.com/news/health-news/articles/2019-05-10/many-drug-abusers-use-family-members-to-opioid-shop

®

®